Image Metabolisms

NOV. 1, 2025 - MAR. 28, 2026The Southern Alberta Art Gallery Maansiksikaitsitapiitsinikssin, CA

Exhibition Text by Adam Whitford

( Installation View, Image Credit: Blaine Campbell )

( Installation View, Image Credit: Blaine Campbell )

As the Gallery’s 2025 Artist-in-Residence at the Gushul Studio in Blairmore, AB, Valladares researched both the historical and current scale of industrial coal and bitumen extraction in the Crowsnest Pass and across Alberta. While at a museum in the Crowsnest Pass, Valladares encountered a diagram titled “What Mankind Owes to a Lump of Coal” that is partly reproduced in the gallery. Beginning with coal and expanding out in a complex web, the drawing depicts just how intertwined ancient life is in the products and chemical processes of today, composing anything from tar, to cotton dyes, and perfumes.

Coal and bitumen have been tied to image-making from the start. The process termed Heliography (from the Greek helios, meaning “sun”, and graphein, meaning “writing”) by French inventor Joseph Nicéphore Niépce (1765–1833) was used to create the oldest surviving photograph, View from the Window at Le Gras (c. 1826–27). The Heliograph used Bitumen of Judea, a naturally occurring asphalt, mixed with lavender oil and exposed to sunlight through a camera obscura. The UV light hardens the bitumen mixture onto a metal plate, rendering it insoluble. The first photograph was quite literally inscribed in fossil fuels.² Niépce, along with his brother Claude, were already quite familiar with combustion and hydrocarbons. In their work as inventors, they also produced the world’s first internal combustion engine nearly 20 years prior.

In dialogue with the entangling of photographic history, extraction, and the mythology of fossil fuels, Valladares creates images in a process similar to Niépce’s Heliographs. Small metal plates, coated with bitumen, bare the faint traces of southern Alberta landscapes and the traces left by the coal mining industry. Valladares’ dialogue with the origins of photography brings to light the oft forgotten connections between image-making and the combustion of buried life. In this instance, the camera and the combustion engine are not so different. Both are contained systems, exposing fossil fuels to fire (whether that of the sun or the combustion chamber) to achieve the desired result. Valladares’ photos are membranes of “buried sunshine”. Once dug up, this petrochemical ancient life undergoes a kind of double exposure, formed by the sun in its first life to be reconstituted onto a plate millions of years in the future for the sun to alter its form once again.

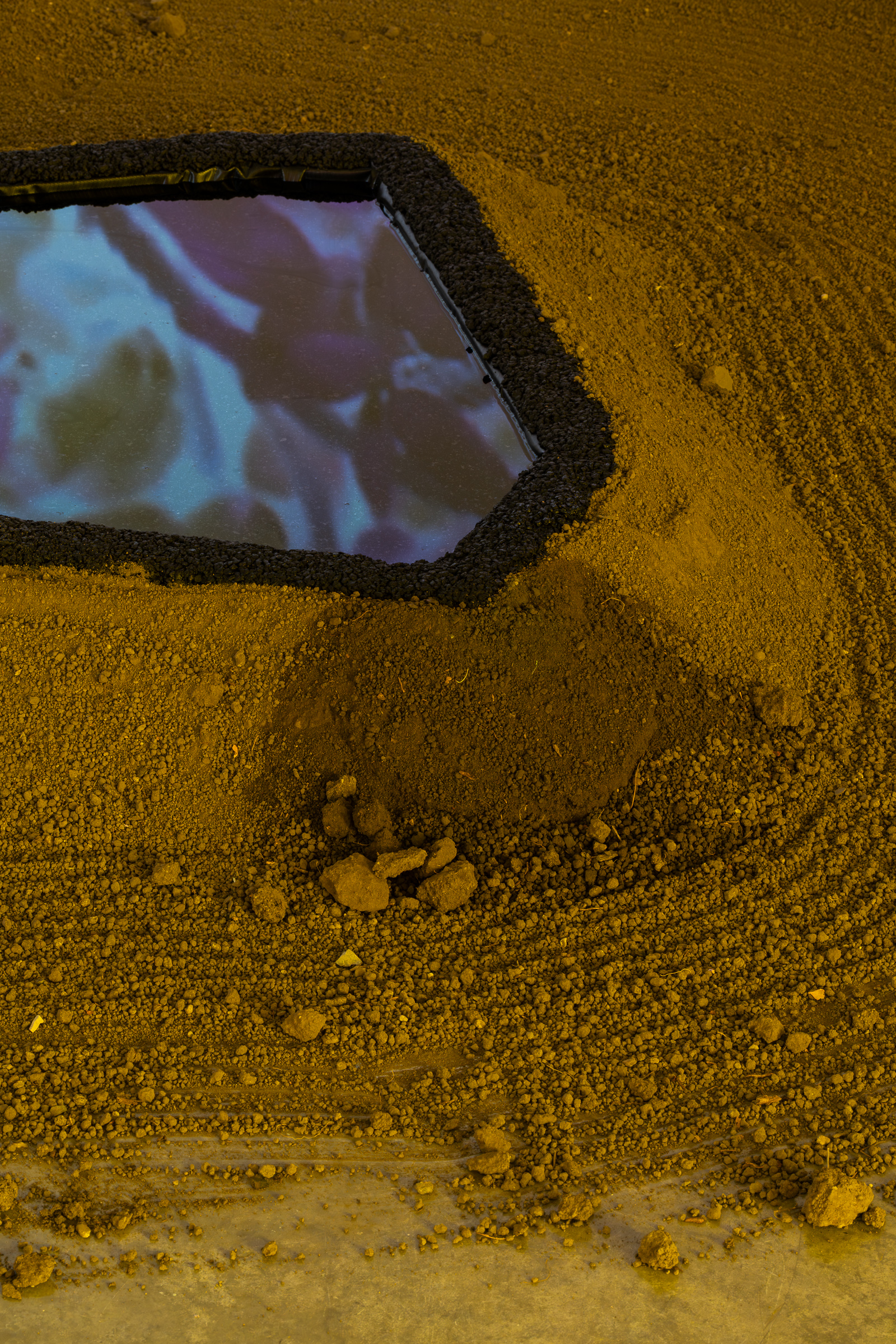

Shaping movement through the gallery, soil is piled and raked into shapes that simultaneously recall rock gardens and the scars of the strip mine. Around the stepped and terraced earth, bundles of lavender are placed in votive offerings, gestures of appreciation for the ancient fossilized life that has fueled photography and innumerous other chemical processes. The lavender’s floral scent, enhanced by lavender oil in a trickling fountain, diffuses Niépce’s original developer into the atmosphere of the exhibition.

Curated by Adam Whitford, Curator & Exhibitions Manager

Preparators: Arianna Richardson (Lead Preparator), Rachael Chaisson, D. Hoffos

Exhibition Modeling: Daniel Reyes Sanders

Sound Design: Haamid Rahim ( Blank Works Studios )